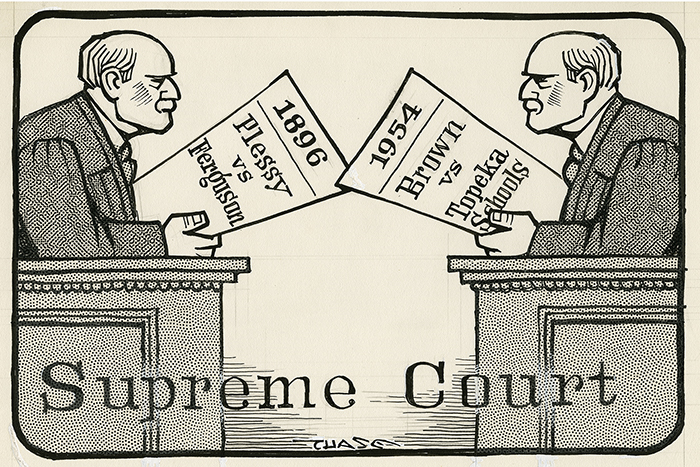

Progress cannot be stopped. However, history teaches us that it can be delayed, and in some cases by many decades. Segregation in the US was officially legalized at the Federal level in 1896 with the Supreme Court decision in the Plessy vs Ferguson case, and ended legally in 1954 with the Supreme Court decision in the Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka case. For 58 years, the doctrine “separate but equal” was the legal framework for racial injustice, oppression, and humiliation to the detriment of African-American people.

Progress cannot be stopped. However, history teaches us that it can be delayed, and in some cases by many decades. Segregation in the US was officially legalized at the Federal level in 1896 with the Supreme Court decision in the Plessy vs Ferguson case, and ended legally in 1954 with the Supreme Court decision in the Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka case. For 58 years, the doctrine “separate but equal” was the legal framework for racial injustice, oppression, and humiliation to the detriment of African-American people.

On June 7th, 1892, Homer Plessy, a brave young man from New Orleans, bought a first class train ticket, and sat in a whites-only car. Although his skin complexion was quite light, he deliberately declared himself as black. He was arrested, charged, and convicted of violation of Louisiana’s racial segregation laws. The decision was made by John H. Ferguson, Judge of Section A Criminal District Court for the Parish of Orleans.

On June 7th, 1892, Homer Plessy, a brave young man from New Orleans, bought a first class train ticket, and sat in a whites-only car. Although his skin complexion was quite light, he deliberately declared himself as black. He was arrested, charged, and convicted of violation of Louisiana’s racial segregation laws. The decision was made by John H. Ferguson, Judge of Section A Criminal District Court for the Parish of Orleans.

Plessy’s appeal to the Supreme Court wasn’t successful as the judges ruled that separation is legal as long as the facilities for whites and blacks are equal. The documents that the judges had at their disposal to make this decision were: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the US, the US Supreme Court decision on the Amistad case, as well as some statements of Thomas Jefferson, and other documents.

The Declaration of Independence (1776) stated that “all men are created equal,” and “they are endowed (…) with certain unalienable rights (…) among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” That means that people have the right to live, to be free, and to prosper. As we all know from American history, blacks, slaves, and women were not included in the phrase “all men.”

Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, himself deeply believed in the inferiority of the black race. In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), he doubted the ability of the slaves to follow and understand math and geometry, and believed that “they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.” He firmly objected to the emancipation of the slaves.

In his letter to Henri Gregoire (1809), Thomas Jefferson again confirmed his beliefs in the inferiority of the black race, although he suggested that it should not determine their rights. “… whatever be their degree of talent it is no measure of their rights.” Jefferson gave an example with the British scientist Isaac Newton who discovered the laws of motion and universal gravitation, and who obviously was much more clever than most of his contemporaries. However, Newton “was not lord of the person or property of others.”

inferiority of the black race, although he suggested that it should not determine their rights. “… whatever be their degree of talent it is no measure of their rights.” Jefferson gave an example with the British scientist Isaac Newton who discovered the laws of motion and universal gravitation, and who obviously was much more clever than most of his contemporaries. However, Newton “was not lord of the person or property of others.”

An interesting precedent in the US jurisdiction during that period, as far as race was concerned, was the Amistad case (1841). A rebellion on the schooner Amistad in 1839 resulted in the capture of all Africans on board. The case ended up at the US Supreme Court that ruled that all captured Africans on board of the Amistad schooner should be given liberty. In his Argument, John Quincy Adams, former US President who represented the captured Africans in court, insisted that the US Constitution recognize slaves as persons and not as property. “The words slave and slavery are studiously excluded from the Constitution. Circumlocutions are the fig-leaves under which these parts of the body politic are decently concealed,” he stated. Due to the clarification that slaves were persons and not chattel, Adams referred to the Declaration of Independence and its recognition that all men had “a right to life and liberty.”

Indeed, if we read Article I, Section 2, Paragraph 3 of the Constitution of the US, we would see that the text referred to “the whole Number of free Persons” who were counted “according to their respective Numbers”, to “Indians” who were not taxed, and to “all other Persons” who were counted as three-fifths each. It is not difficult to guess that these persons were the slaves and they were not even counted as a whole number each.

The Plessy vs Ferguson decision was very much influenced by the way the members of the Supreme Court at that time understood federalism in the US. The Tenth Amendment stated that rights that the US Constitution did not give to the Federal government or specifically forbid the states from exercising, could be regulated by the states or by the people of these states. The Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed that all residents of the US were equal in front of law, and that “no State can deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Section 5 of the Amendment obliged Congress “to enforce, by appropriate legislation” that this document took effect. The section actually authorized Congress with greater power than the power regulated by the Tenth Amendment.

In 1883, the Supreme Court’s decision on 5 Civil Rights Cases suggested that “it is absurd to affirm that” Congress would guarantee the equal protection of the law in every state, and in every case. It would “make Congress take the place of the state legislatures and to supersede them.” The opinion implied that states themselves had the power to correct state violations of rights to life, liberty, and property. Private acts of racial discrimination were simply private wrongs that the national government was powerless to correct.

The Majority Opinion (6-1) in the case Plessy vs Ferguson declared that state legislatures had the right to pass “laws permitting, and even requiring [racial] separation, in the places where [races] are liable to be brought into contact.” The Court considered the basic flaw in Plessy’s argument “the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority.” If separation made African Americans feel unprivileged, this was not because of the intention of separation, but because they themselves had decided so.

The Court could not accept laws that tried to abolish racial prejudices because its members believed that laws were not able to enforce social equality, and “it must be the result of natural affinities, a mutual appreciation of each other’s merits, and a voluntary consent of individuals.” This decision upheld the doctrine “separate but equal” because it didn’t see the separation as a racist violation of human rights. It stated that although separate, the two races had equal rights.

The Dissenting Opinion in this case declared that “Our Constitution is color-blind” because it didn’t speak about “superior, dominant, ruling class or citizens,” and it “neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” On the contrary, the “real meaning” of the Louisiana segregation law was based “on the ground that colored citizens were so inferior and degraded that they could not be allowed to sit in public coaches occupied by white citizens.” According to the Dissenting Opinion, this law planted “the seed of race hate”, created “a feeling of distrust between these races,” and therefore was unconstitutional.

The US Supreme Court decision in the Plessy vs Ferguson case (1896) had a huge impact on preserving the racial injustice in the country. The decision legitimized the segregation by stating “separate but equal”, and it regulated the American way of life for many decades. It was another famous legal case, Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka (1954), that brought this doctrine to an end.

The US Supreme Court decision in the Plessy vs Ferguson case (1896) had a huge impact on preserving the racial injustice in the country. The decision legitimized the segregation by stating “separate but equal”, and it regulated the American way of life for many decades. It was another famous legal case, Brown vs Board of Education of Topeka (1954), that brought this doctrine to an end.

However, it took a lot of efforts, time, and hard work of a large group of black attorneys, appointed by the NAACP, and under the leadership of Charles Hamilton Houston. Thurgood Marshall, who later became the first African-American Justice in the US Supreme Court, was a part of this legal “dream team”, among other big names. Houston himself spent many months travelling in different states to film “white” and “colored” schools, and to prove that in most cases they were far from equal.

To build their final case, the attorneys focused on four states – Kansas, Delaware, South Carolina, and Virginia. In all 4 states the schools were segregated by law, and the NAACP position was that segregated schools by definition ment inequality. The lawyers challenged Plessy vs Ferguson decision that “if separation makes African Americans feel unprivileged, this is not because of the intention of separation, but because they themselves have decided so.”

The four trial courts ruled against the NAACP, and the case went to the US Supreme Court where the historic decision was made. The Justices wrote that “segregation is per se inequality,” and it “has a detrimental effect on colored children, especially when it is enforced by law.” They concluded that “in the field of public education the doctrine ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Although this decision was unanimous, it didn’t specify when and how desegregation was to be achieved. Many brave men, women, and children struggled for decades to overcome racial prejudices and distrust, and to create integrated schools, where diversity and inclusiveness were self-evident. It wasn’t an easy goal, and yet, it is not. Even now in 2017, we can still argue if American public schools are fully desegregated.

Leave a comment